- April 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

In May of 2017, Dr. Pamela Carbiener lost a young woman in her emergency room whom she had watched grow up.

The woman was addicted to heroin and any opioid she could inject in her body. Carbiener said at that point, the addiction was too strong. The woman developed a heart infection that ultimately killed her.

“There was no 2017 medicine that could’ve saved her life," Carbiener said. "It was that bad. You couldn’t help her.”

That young woman was one of the many suffering from opioid disease in Volusia County.

Carbiener, who is an obstetrician at Halifax OBGYN, said the opioid epidemic became apparent to her a little over five years ago when she worked at the county health department's free pre-natal health clinic, which has since been shut down. She said at the clinic's closing, the majority of the women coming in were pregnant women addicted to opioids. Over the years, Carbiener said she's seen the opioid epidemic increase despite the efforts of State Attorney Pam Bondi and the initiative to shut down pill mills.

“By then, the culture of opioid use had become entrenched and while it was a really good thing to shut down those pill mills and a really good thing to punish those physicians that were propagating that misbehavior, it maybe only caused a little bit of a plateau and then it’s gone back up," Carbiener said.

From her perspective, she said Volusia County seems to be worse per capita compared to bigger cities like Orlando and Jacksonville due to the larger number of babies recovering from opioid addictions they received from their birth mothers.

Why is it worse in Volusia? Carbiener called that the "million dollar question."

Sheriff Mike Chitwood called the local opioid crisis his biggest challenge in 2018.

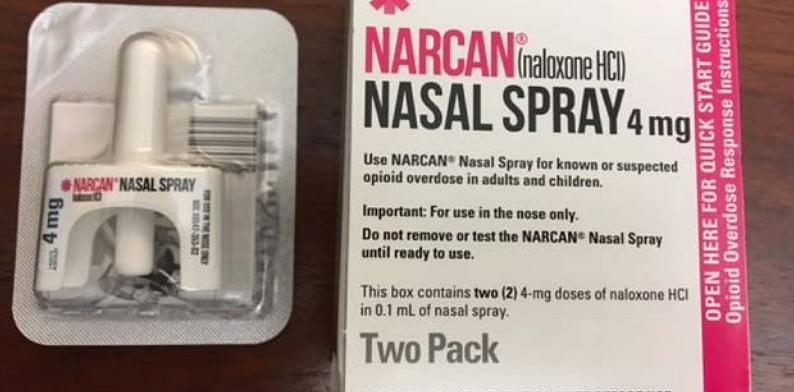

Last year alone, Volusia County had an estimated 850 uses of Narcan, a medicine to reverse an opioid overdose and block its effects. In the past, Chitwood said they used to treat overdose deaths as just someone who made a conscious choice and died as a result of illegal activity.

Now, they treat each overdose case like a homicide. They investigate who the victim, 100 of which died last year, received the drugs from and try to prosecute them for manslaughter. However, Chitwood said that when they addressed drug problems in the past, namely methamphetamines in 2006 and pill mills in 2010, they only attacked supply and not demand — meaning those addicted moved on to the next drug.

“We never put enough money in for treatment," Chitwood said. "We just kept smashing the doors down and locking up the dealers, and occasionally lock up these people, only to realize now, all these years later, these people, these folks have a disease.”

It's why he said he's advocating for restoring funding for Stewart-Marchman-Act Behavioral Healthcare. He said its funding was cut by 40% last year, resulting in roughly 1600 people who came to them for help having to be turned away.

Flagler County is no exception to the opioid epidemic. In October, the county's sheriff's office worked with VCSO to dismantle a multi-county heroin ring.

"We have no way of knowing how the future will trend but in Flagler County we’re doing all that we can to get this epidemic out of our community," said Brittany Kershaw, FCSO public affairs office manager in an email.

Carbiener calls the opioid crisis our generation’s Bubonic Plague, Spanish Influenza, Cholera and HIV epidemic.

She said nationwide, physicians are seeing patients come in with diseases caused by opioid addiction they haven't seen in high volume in over fifty years, like bacterial endocarditis, where bacteria enters the heart valves and destroys them. Her youngest patient to get a valve replacement was 21.

Another of her patients died from an infected clot in the back of her neck that prevented her from breathing.

One the challenges she recognizes in 2018 is getting physicians to treat opioid addicts on an outpatient basis. She said often doctors are afraid of the liability these "high-risk" patients present.

“You don’t get to choose the era in which you became a physician, and the physicians that became physicians during the bubonic plague and the Spanish flu and the HIV epidemic, they had decisions to make," Carbiener said. "Are they going to be physicians, or are they going to be selfish? And I think it’s selfish not to take care of these patients.”

In order for care to increase, she said compassion also needs to grow. Doctors and the community need to work together to help those suffering from opioid addiction find a safe place to stay, a stable job and transportation. The solutions are not going to come from the federal and state government, but from the private sector, she said.

“These patients are not infectious," Carbiener said. "This epidemic is entirely where the parallel ends.”